In 2003, a striking phenomenon unfolded in Guangzhou’s Fangcun Tea Market: products labeled as “Taiwan Alishan High Mountain Oolong Tea” were sold at the astonishing price of 6,000 RMB per jin (about 500g). In a market that gathers thousands of tea varieties, such a high-priced product managed to carve out its own niche. The price itself was jaw-dropping, but an even more pressing question emerged: among the countless semi-ball-rolled teas, and when judging only by dry leaf aroma, how many consumers could truly identify the tea’s authentic origin?

As a centralized tea hub, Guangzhou Fangcun attracted buyers nationwide and witnessed the remarkable rise of Taiwan-style teas in the mainland market. However, as the sourcing of Taiwan-style teas grew increasingly complex—from direct shipments from Taiwan, re-exports through Southeast Asia, to imitations in Fujian—consumers faced an unprecedented challenge of discernment. Behind a cup of Alishan tea priced at 6,000 RMB lay intricate market logic and deep consumer misconceptions.

In the following, we will explore the reasons behind this phenomenon, the acceptance of such high-priced teas in the market, and how consumers can make wiser choices in the complicated landscape of Taiwan-style teas.

Guangzhou Fangcun: The Barometer of Mainland Tea Trade

The Guangzhou Fangcun Southern Tea Market holds a pivotal role in mainland China’s tea industry. Spanning 103,052 square meters, it accommodates around 1,500 merchants, with an annual trade volume of 1.3 billion RMB. Founded in 2000, Fangcun specialized in wholesale tea, along with teaware and tea crafts, offering over 1,000 tea varieties.

Within this tea kingdom, one could find Zhejiang’s Longjing, Guangdong’s black tea, Fujian’s Tieguanyin, Yunnan’s Pu’er and tuocha, Guangxi’s scented teas, and of course, Taiwan’s Dong Ding Oolong. Amid such diversity, Taiwan-style tea gradually stood out with its signature fragrant character, eventually evolving into a market miracle that could sustain a 6,000 RMB price point.

Fangcun was not just a trading hub—it was a barometer of the mainland tea industry. For example, the second Guangzhou International Tea Culture Festival in 2001 attracted more than 80,000 visitors and generated 500 million RMB in transactions. Success at Fangcun amplified Taiwan-style tea’s influence nationwide, fueling consumer attention and demand across China.

The Market Logic Behind the 6,000 RMB Price

For Alishan tea to command 6,000 RMB per jin, several market dynamics were at play. First, mainland consumers’ purchasing power for premium teas surged, echoing Taiwan’s high mountain oolong boom of the 1990s.

Second, scarcity perception played a critical role. Unlike the abundant supply of mainland teas, Taiwan high mountain oolong carried a unique cultural cachet. The “Taiwan Alishan” label itself implied rarity and premium quality, reinforcing psychological willingness to pay more.

Furthermore, Taiwan-style tea established new value benchmarks in the mainland. When a tea sold for 2,000 TWD in Taiwan could fetch 2,000 RMB across the strait, the profit gap underscored vast market potential. A 6,000 RMB Alishan tea, though steep, was not entirely illogical within such an environment.

The Challenge of Complex Origins

Yet, high prices came with a hidden problem: the increasingly complex origins of Taiwan-style teas made authenticity nearly impossible to verify. Mainland “Taiwan-style tea” generally came through three channels: genuine Taiwanese high mountain oolong shipped directly, Southeast Asian-grown teas re-exported to China, and oolongs produced in Fujian.

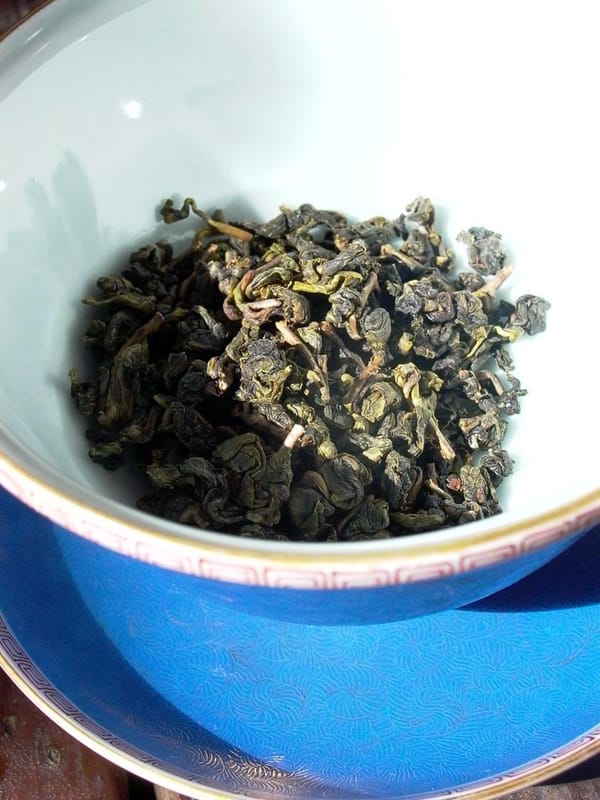

All of these emphasized the hallmark of lightly fermented, semi-ball-rolled oolong, and were thus collectively marketed as “Taiwan-style tea.” Even veteran tea drinkers struggled to distinguish origins by appearance or dry aroma alone. Identifying varietals like Qingxin Oolong versus Jinxuan was already challenging, while pinpointing geographic provenance required expert-level training.

This ambiguity created room for manipulation. Some vendors exploited consumer blind spots by passing off cheaper teas as premium Taiwan imports. In Anxi, some even adopted Taiwanese accents to market local teas as “Taiwan-style,” raising Fujian light-oxidized oolongs’ perceived value.

Consumers’ Dilemma

Consumers thus faced a dilemma. On one hand, they longed for authentic Taiwan high mountain teas and were willing to pay fairly. On the other, without expertise, they struggled to judge authenticity among numerous Taiwan-style offerings.

This was especially true for the 6,000 RMB Alishan case: such a price carried high risk but reflected the deep desire for top-tier teas. The question was whether the quality matched the price, or whether it merely reflected brand premium tied to the “Taiwan Alishan” name.

Traditional evaluation methods often failed when teas shared similar processes. Thus, consumers needed new benchmarks: storability, cultivar traits, processing details—all requiring knowledge and experience.

The Gap in Market Education

This phenomenon largely stemmed from insufficient consumer education. While demand for Taiwan-style teas was strong, lack of knowledge left buyers vulnerable to speculation and exploitation.

Effective education should cover cultivar knowledge, processing features, and quality benchmarks. Consumers should learn the traits of Qingxin Oolong, Jinxuan, Cuiyu, and recognize key features of Taiwan light-oxidized oolongs: bright honey-green liquor, elegant high aroma, and sweet, smooth taste.

They also needed awareness of origin value. Taiwan direct teas offered higher assurance; Southeast Asian teas might compromise freshness; mainland Taiwan-style teas differed in terroir. Armed with such knowledge, buyers could align purchases with budget and preference.

Brand Premium vs. Actual Quality

The 6,000 RMB Alishan phenomenon highlights tension between brand value and real quality. Willingness to pay for cultural branding marks market maturity, but only when backed by verifiable quality differences.

Alishan’s high-altitude terroir indeed supports superior tea cultivation. Yet, geographical prestige must align with actual sensory quality—aroma, flavor depth, endurance, storability—for brand premiums to be justified. Without this, branding risks devolving into hollow speculation.

The Need for Market Standardization

The Fangcun phenomenon underscores urgent need for market regulation. In a fragmented, opaque environment, consumer rights and premium products both suffer.

Standardization must include clear origin certification, craft benchmarks, and grading systems, alongside effective enforcement against counterfeiting and false marketing. Industry self-discipline also matters: vendors must disclose true origins and processing details. Only with transparency can consumers choose fairly.

Rational Consumption: The Wise Choice

For consumers, rationality is key. Faced with 6,000 RMB teas, they must weigh actual needs and affordability, avoiding blind pursuit of price or prestige.

First, value lies in experience and culture, not mere price. A tea that fits one’s palate and budget often surpasses overpriced “status teas.”

Second, investing in tea knowledge and tasting skills empowers informed decisions. Over time, this yields lasting benefits in discerning quality.

Lastly, choosing reputable merchants mitigates risks. Building long-term trust allows gradual familiarization with tea differences, enhancing consumer confidence.

The 6,000 RMB Alishan phenomenon reflects both dynamism and challenges in China’s tea evolution. Only through sustained education, regulation, and rational consumption can the market mature healthily.