In 1979, when Taiwan’s tea market was still exploring how to price high-quality teas, a tea farmer named Su Shitie made a bold decision: he launched his carefully crafted Dong Ding Oolong Tea at an astonishing price—NT$800 for half a jin, equivalent to NT$1,600 per jin. At that time, this price was jaw-dropping. Yet the market response proved his foresight. The tea sold out completely and became the benchmark for premium Taiwanese tea pricing, opening the golden era of Dong Ding Oolong Tea.

Su Shitie’s success was no coincidence. It was built upon his uncompromising pursuit of quality. Through his high-price, high-quality strategy, his Dong Ding Oolong Tea became a “dream tea” for enthusiasts, setting a new value standard for Taiwanese fine tea and influencing the entire tea industry throughout the 1980s.

In this article, we will explore how Su Shitie created this legend, examine the brilliance of Dong Ding Oolong Tea in the 1980s, and reflect on the golden era’s lasting impact on Taiwan’s tea industry.

Su Shitie’s Quality Revolution

The release of Su Shitie’s Dong Ding Oolong Tea in 1979 represented a major breakthrough in Taiwan’s awareness of tea quality. At the time, most teas were priced by volume, and few dared to challenge the market with such a high price. Yet Su Shitie believed that excellent tea deserved its value. His strategy became a milestone in the rise of Taiwanese fine tea.

This pricing success revealed the hidden demand among Taiwanese consumers for quality. Su’s ability to sell out his tea showed that Taiwan had the necessary foundations for developing a premium tea market: refined processing techniques, discerning consumers, and a market environment willing to pay for excellence.

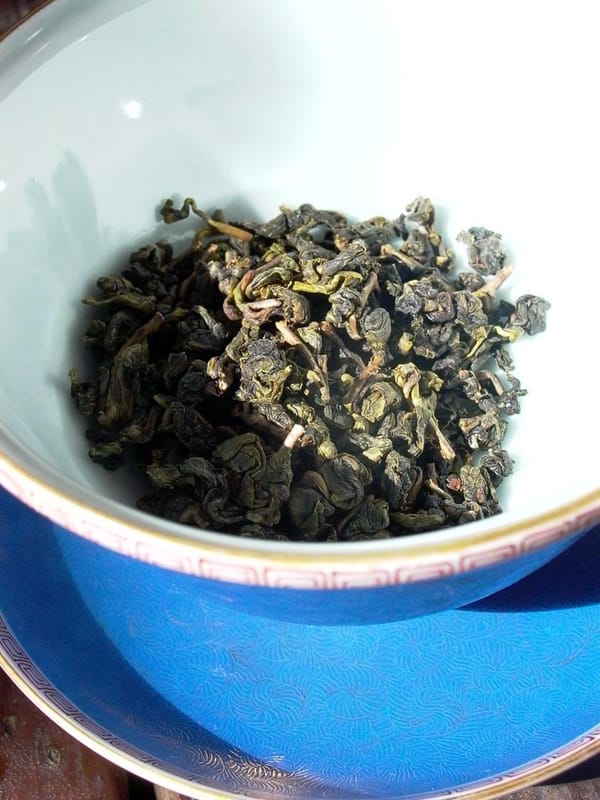

Dong Ding Oolong’s unique strengths were also key. As a representative of the Qingxin Oolong varietal, it offered remarkable storage potential and complex flavor layers. With proper medium fermentation, the tea produced a golden liquor, full-bodied taste, and a distinctive lingering sweetness—all essential qualities for high-end tea appreciation.

The Glory of Dong Ding in the 1980s

The high-price model Su Shitie pioneered blossomed throughout the 1980s. Medium-altitude oolong teas, especially from Dong Ding, gained fame for their outstanding performance. During this era, Dong Ding Oolong not only achieved excellence but also established Taiwan’s reputation for fine tea internationally.

In this period, Dong Ding teas followed traditional medium-fermentation processing, emphasizing richness and lingering sweetness. Shaped into semi-ball form through labor-intensive rolling, these teas brewed golden infusions with strong endurance (“pao shui,” the ability to withstand multiple infusions). Their mellow taste and deep hui gan (returning sweetness) defined the mainstream of the time.

This success also shaped competition standards across Taiwan’s tea regions. Dong Ding’s reputation elevated Nantou’s Lugu Township and inspired tea farmers elsewhere to adopt its methods, hoping to replicate its model of success.

Exemplars of Tradition

The golden era brought forth many artisans who remained loyal to traditional craftsmanship. Among them, Chang Shih-rong of Kunyuan Tea Factory in Guangxing Village, Lugu, stood out. Working from his old Sanheyuan courtyard, he produced Dong Ding Oolong with authentic flavor, preserving tea samples since the 1970s to document quality changes over time.

Proud of pricing his teas high during the boom, Chang believed quality and fair value went hand in hand. His business thrived, as he said: “I never have to worry about economic downturns!” Consumers who bought his tea often became loyal followers, drawn to its deep, original taste. His case demonstrated that true quality cultivates stable clientele without the need to chase fleeting trends.

Success on the Global Stage

Dong Ding Oolong’s influence extended beyond Taiwan. A remarkable example is Huang Haoran, an engineer-turned-tea entrepreneur. After giving up alcohol for tea, he opened a tea house in Tokyo and later expanded into Taiwan, running establishments dedicated to pairing tea with cuisine. His insistence on authentic Dong Ding flavor won strong recognition among Japanese tea drinkers.

Huang’s ventures, such as “Zhuli Hall” for casual tea service and the more refined “Chajiu Hall,” revealed his mission-driven approach: spreading the pure taste of Taiwanese oolong to the world. His story showed that Dong Ding Oolong had achieved world-class recognition and that adherence to authenticity could earn international respect.

The Value of Tradition

The golden era’s success was largely due to fidelity to traditional methods. Even as market trends shifted toward lightly fermented, fragrant teas, many artisans held fast to medium fermentation, believing it best expressed Qingxin Oolong’s essence.

Producers like Chang Shih-rong argued that while this style did not always win awards in competitions favoring lighter teas, it created teas of deep resonance and enduring charm. Their persistence preserved precious know-how and offered consumers authentic alternatives.

The shared challenge was how to preserve oolong’s original taste while ensuring both value and longevity. Artisans of both primary processing (like Chang) and refined finishing (like Huang) contributed to maintaining this authentic path.

The Art of Balancing Quality and Value

The true significance of Su Shitie’s NT$1,600 legacy was the balance it struck between quality and value. He demonstrated that consumers would pay fair prices for genuinely outstanding tea, a shift that reshaped Taiwan’s tea industry.

This was not simply price inflation but the result of meticulous craftsmanship. Su’s success revealed that only teas of genuine excellence could support premium prices. This quality-driven philosophy became a guiding principle for Taiwanese fine tea development.

High-quality Dong Ding Oolong also proved an ideal investment. Not only could it sell at high prices upon release, but with time, its value often increased. This “value preservation” made fine oolong both a cultural treasure and a stable source of income for producers.

The Era’s Lasting Significance

Su Shitie’s 1,600 NT legend marked a turning point from quantity-driven production to quality-driven value. It redefined Taiwan’s tea identity, shifting the industry toward branding and craftsmanship rather than volume alone.

This era also highlighted Taiwan’s capacity for innovation. By refining traditional techniques, tea farmers created products of international competitiveness and prestige. Though later eclipsed by high-mountain oolongs, the standards set by Su Shitie and his peers remain foundational. The golden era reminds us that truly excellent tea always finds its market—the key lies in preserving quality and connecting with those who appreciate it.