When you cradle a steaming cup of black tea, have you ever wondered why English calls it "tea" instead of "cha"? Behind this seemingly simple linguistic shift lies a sweeping tale of East-West trade, where a small leaf from the mountains of Fujian transformed into liquid gold that conquered Europe's royal courts.

The Language Code: Tracing “Cha” to “Tea” Through Geography

Originally, British society used “cha,” a pronunciation influenced by overland trade routes from northern China. However, once the British East India Company began importing Wuyi black tea from Xiamen, everything changed. Following the Xiamen dialect, the British adopted “tea,” marking not only a change in pronunciation but also a shift in trade routes—ushering in the maritime Silk Road and the age of black tea.

Due to Wuyi rock tea's (referring to black tea at the time) dark liquor color, the British dubbed it “black tea,” a term that remains the global standard today. This simple linguistic evolution reflects a historic pivot—from land to sea, from green to black tea.

Next, we’ll explore the fierce competition between the Dutch and British for control of the tea trade and how Wuyi black tea made its way into Europe’s highest echelons, shaping global tea culture.

Tea Wars of the Trading Empires

The Dutch Advantage

In 1607, the Dutch East India Company first acquired Wuyi black tea from Macau in southern China, then re-exported it via Java to Europe. At the time, Japanese green tea dominated the European market. But the rich and bold flavor of Wuyi black tea quickly outshone its competitors, taking over the tea trade. By 1650, the Dutch nearly monopolized the European tea business.

Britain’s Strategic Counterattack

Seeing the potential of Chinese tea, the British East India Company established a trading post in Xiamen in 1644, initiating fierce competition with the Dutch. The intensity of this commercial rivalry sparked two Anglo-Dutch Wars (1652–1654 and 1665–1667). The immense profits from Chinese tea had triggered international conflict.

After winning both wars, Britain broke the Dutch monopoly. In 1669, the British government granted exclusive tea trading rights to the East India Company, cementing black tea as Europe’s preferred variety and establishing Britain’s long-standing dominance in tea trade.

The Royal Fascination with the Orient

A Tea-Drinking Royal Trend

In 1662, Portuguese princess Catherine brought black tea and porcelain teaware as part of her dowry to England. She promoted replacing alcohol with tea at court, sparking a royal craze for Chinese tea. This Iberian princess became an accidental founder of British tea culture.

Queen Anne helped popularize tea at breakfast, and in 1840, afternoon tea became a national movement. Queen Victoria drank black tea daily, helping it spread from aristocratic luxury to a national staple. Even the Queen of France was intrigued, demanding to know the “secret behind the red liquor in tall glasses.”

Pricing Down, Popularity Up

In 1664, the East India Company gifted King Charles II two pounds of Wuyi black tea—then worth 40 shillings per pound, a luxury beyond the reach of commoners. By the reign of George I (1714–1729), prices had dropped to 15 shillings per pound.

This price drop made tea accessible beyond royalty. Literati and scholars began to embrace black tea, a classic case of luxury democratization and a hallmark of globalized trade.

A Social Revolution Steeped in Tea

The Rise of the Tea Party

Wuyi black tea revolutionized social interaction in Britain. Tea gatherings, or “tea parties,” became a new cultural phenomenon. Poets like Joseph Addison and Samuel Johnson hosted lively tea sessions in London, where Wuyi black tea became the drink of the day.

In 1717, Thomas Twining opened the Golden Lion in London, the first tea shop catering to women. By 1732, “tea gardens” emerged where families could enjoy tea together. Tea culture broke free from male-dominated coffeehouses, creating inclusive social spaces.

Tea in Literature and the Arts

Wuyi black tea captured not only palates but hearts. In 1711, poet Alexander Pope praised it:

“Silver lamps on Buddha’s altar glimmer, steam rises from Chinese porcelain.

Red flames blaze with elegance, suddenly filling the air with fragrant charm.

The silver teapot pours fiery liquor—this splendid tea party is truly alive!”

Poets likened black tea to goddesses and suitors. In 1725, Edward Young wrote:

“Crimson lips stirred the breeze; cooled the Wuyi tea, warmed the lover’s heart—even the Earth rejoiced.”

Even Lord Byron confessed, “I must turn to Wuyi tea...”

Crossing the Atlantic: America’s Tea Fever

Rise of the American Tea Trade

Britain’s black tea mania crossed the Atlantic. In 1784, merchants from New York and Philadelphia raised 120,000 silver dollars to outfit the Empress of China, a 360-ton vessel bound for Canton. It returned with 2,460 dan of black tea and 562 dan of green tea—all sold under the name of “Chinese tea.”

By 1800, the U.S. began importing high-grade Lapsang Souchong (Zhengshan Xiaozhong). In 1810, black and green tea imports were equal. By 1844, when the Treaty of Wangxia was signed, U.S. tea imports had reached 149,311 dan. Wuyi and Lapsang Souchong remained America’s favorites, becoming cornerstones of transpacific trade.

Conclusion: How a Leaf Reshaped the World

From “cha” to “tea,” the evolution of a single word traces the path of Chinese tea conquering the globe. Wuyi black tea transformed not only European tastes but also redefined social customs, fueled global trade, inspired literature, and even sparked wars. A single leaf carried the weight of East-West cultural exchange.

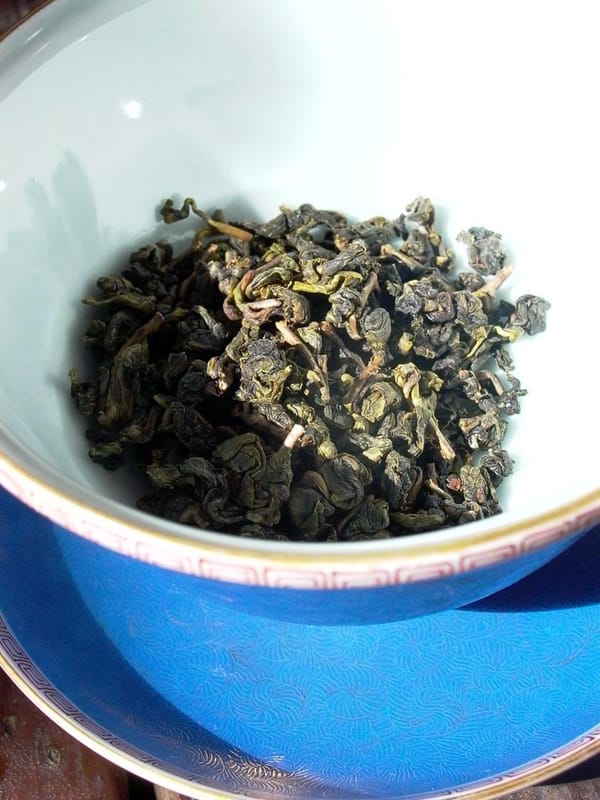

Modern tea lovers seeking to relive this legend should start with authentic Zhengshan Xiaozhong. In its pine-smoked aroma and mellow infusion lies a legacy three centuries deep. Pair it with an exploration of traditional teaware, and you’ll understand how black tea pushed even European porcelain craft forward.