A Literary Giant with a Humble Love for Tea

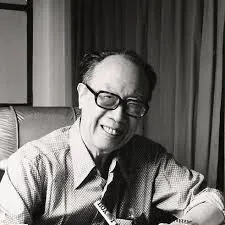

Liang Shih-chiu was a renowned translator in modern Chinese history, best known for spending nearly 40 years translating the complete works of Shakespeare—an achievement that remains unmatched. He also compiled English-Chinese dictionaries and wrote millions of words in essays.

In his celebrated collection Yashe Essays, Liang often wrote about his love for food and tea. Yet, in his typically humble and humorous style, he insisted that he didn't truly understand tea. He once wrote:

“I’m not good at tasting tea, I don’t understand The Classic of Tea, and I know nothing about tea ceremony. I’ve never experienced the ‘gentle wind rising from beneath the arms.’”

A Lifelong Journey with Tea

Over the decades, Liang tasted a wide variety of teas: Beiping’s double-scented tea, Tianjin’s big leaf, West Lake’s Longjing, Lu’an’s Guapian, Sichuan’s Tuo tea, Yunnan’s Pu’er, Dongting’s Junshan tea, and Wuyi’s Rock tea. He even tried lesser-known varieties such as tea stems and “gaomo’er” (tea dust), which might not be appreciated by connoisseurs but were part of his daily life.

Born in Hangzhou, raised in Beijing, and later moving to Taiwan, Liang remained inseparable from tea—enjoying Longjing, jasmine tea from Beijing tea shops, and Taiwan’s oolong.

He recalled his childhood:

“In the house, there was a large teapot kept in a rattan basket lined with cotton for insulation. We helped ourselves. We used ‘mung bean bowls’—large ones for rice, smaller ones for tea—greenish in color, rough and durable. Of course, they couldn’t compare to Song porcelain, Jiangxi porcelain, or Western ceramics, but they had a humble sturdiness that I dearly miss.”

Even in memory, tea lingered. He reminisced about the rattan tea baskets used in his youth (what we now call cha shou), which kept tea warm. He also mentioned a family gaiwan brought back from China after cross-strait relations reopened—though broken, it remained a precious symbol of his tea-drinking past.

He preferred thick, rustic bowls, like those used for mung bean soup. They lacked refinement but had character—and if they broke, no one would scold him. That kind of humor captures the link between his life and tea.

Teas and Varieties Enjoyed by Liang Shih-chiu

| Tea Type | Variety | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Green Tea | Longjing | Tasted in West Lake, exquisite flavor |

| Guapian | Gift from a friend, wild and earthy aroma | |

| Watermelon Tea | A type of Guapian with fruity notes | |

| Yellow Tea | Junshan Tea | Bought at Dongting Lake, needle-like leaves floating upright |

| Oolong Tea | Dong Ding Oolong | Famous in Taiwan, though truly high-quality versions are rare |

| Oolong Tea | Tieguanyin, Da Hong Pao | Enjoyed via gongfu tea prepared by a friend in Qingdao; elaborate utensils and ritual |

| Dark Tea | Pu'er | Drunk in Beiping’s Zhengyanglou, good for digestion |

| Dark Tea | Tuo Tea | From Sichuan, inconsistent quality on the market |

| Other | Double-scented | Purchased in Beiping, rich floral notes (reprocessed tea) |

| Other | Big Leaf | Tasted in Tianjin, limited description |

| Other | Gaomo’er | Affordable tea dust and stems |

| Other | Yu Gui Tea | A family blend of jasmine and Longjing, a private recipe |

Though Liang claimed he didn’t “understand tea,” this list paints a picture of a deeply engaged tea drinker.

The Social Delight of Tea in Liang's Life

To his friends, Liang Shih-chiu's relationship with tea was full of warmth and personality.

Bing Xin, a fellow writer, once said:

“A person should be like a flower—possessing color, fragrance, and taste. Among men, only Liang Shih-chiu is like a flower.”

His daughter Liang Wen-qiao shared:

“After dinner, we’d sit in the living room, drink tea, and chat—mostly about food.”

Though he modestly claimed to be a tea novice, these insights show that Liang was discerning and appreciative when it came to tea—much like his famous essays on food.

He fondly recalled visiting Zhou Zuoren’s Kucha'an (Bitter Tea Hut) before the war, where tea was simple: a light, astringent, green brew. He also described sipping Longjing tea with lotus root powder during a visit to West Lake—a pairing he considered unparalleled.

The Creative Legacy of Yu Gui Tea

One of his elders, Mr. Yu Gui, was a Manchu gourmet who blended jasmine tea and Longjing in equal parts. The result carried jasmine’s fragrance and Longjing’s bitterness—a delightful harmony. The family adopted this custom and named the blend Yu Gui Tea, keeping the recipe as a treasured tradition.

Tea Appreciation and Aesthetic Playfulness

Liang often bought jasmine tea from East and West Hongji Tea Houses in Beijing. He described the scent of fresh jasmine flowers layered on tea leaves as a sensory delight. His humorous writing captured the charm of such moments.

He also wrote about the elaborate rituals of Chaozhou Gongfu tea, with detailed descriptions of zhuni teapots, porcelain cups, and the refined elegance of every gesture.

Through tea, we glimpse the elegance and wit of Liang Shih-chiu’s life—and understand tea's place in his literary world.

SEO Optimization

Tags:

Liang Shih-chiu, Tea Culture, Chinese Literature, Gongfu Tea, Longjing Tea, Pu'er, Jasmine Tea, Yu Gui Tea, Taiwanese Oolong, East Asian Writers

Tags (Chinese):

梁實秋、茶文化、中國文學、工夫茶、龍井、普洱、香片、玉貴茶、台灣烏龍、東亞作家

Excerpt:

Discover how legendary writer and translator Liang Shih-chiu wove tea into his life and literature—from West Lake’s Longjing to homemade Yu Gui Tea. A story of elegance, humor, and the quiet rituals of tea.

SEO-Friendly URL:

liang-shih-chiu-tea-culture-literature