Why does a humble teacup make tea taste smoother?

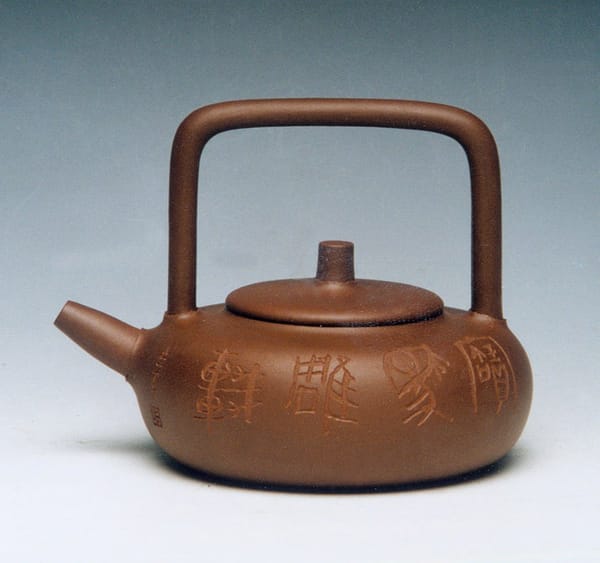

Why does a Yixing teapot seem to grow more "alive" with time?

The answer often lies in a process you can’t see—but that every serious tea lover should understand: sintering.

If you enjoy brewing tea or collecting teaware, learning the basics of sintering will elevate how you select teacups and teapots—not just by their appearance, but by the story told through their inner firing technique. The warmth of the clay, the texture of its surface, the strength hidden within its fragility—all are shaped in this seemingly mundane yet magical transformation.

Today, let’s step into the world of ceramic sintering—a craft that has supported the development of tea culture for millennia—and uncover the science, history, and artistry behind every sip you take.

Sintering: The Critical Moment in Ceramic Birth

Sintering might sound like a technical term, but at its core, it's the "moment of magic" when soft clay transforms into a solid, durable ceramic.

Imagine shaping moist clay with your hands and placing it into a blazing kiln. As the temperature rises, the loose particles begin to approach each other, embrace, and gradually fuse into a unified body. This process allows us to pour hot tea into ceramic cups without worrying about them melting in our hands.

Scientifically, sintering refers to heating powdered materials to a high temperature below their melting point, causing atoms to diffuse and bond together. The particles don’t melt entirely—they "bond" through heat-driven diffusion, creating density and strength without losing their form.

From Ancient Intuition to Modern Science

Thousands of years ago, our ancestors didn’t know the word "sintering," but they mastered its practice. Through trial and error, they discovered how temperature, duration, and airflow affected the quality of fired wares.

China’s ceramic legacy dates back to the Neolithic age. Early kilns were simple, but by the Song and Ming-Qing dynasties, sintering had reached extraordinary heights. The elegance of Jingdezhen porcelain, the tranquil blues of Longquan celadon, and the refined whites of Ding ware are all triumphs of masterful sintering.

Today, we view sintering through the lens of physics and chemistry. Temperature precision, atmospheric control, and timing are scientifically calibrated—turning what was once intuition into repeatable artistry.

The Three Stages of Sintering: A Journey from Earth to Art

Think of sintering as a journey, unfolding in three main stages:

Stage 1: Pre-sintering (Initial Heating)

At around 100–200°C, water physically trapped in the clay begins to evaporate. Slow heating is key—too fast, and steam expansion could crack the ware.

By 500–600°C, chemically bonded water is released, and organic matter begins to burn away. The clay body hardens but remains fragile—just like packing your bags before a long journey: vital, but delicate.

Stage 2: Main Sintering (Transformation)

At 700–900°C, the real transformation begins. Clay minerals break down, new crystal phases form, and particles begin to fuse.

For porcelain, temperatures can rise to 1200–1400°C, forming glassy phases that create translucency and smoothness. Different clay bodies require different sintering temperatures, which is why regional styles vary so widely.

Stage 3: Cooling (Slow Descent)

Once sintering is complete, the kiln must cool gradually. A sudden temperature drop causes cracks due to thermal stress. Proper cooling ensures structural stability and a uniform surface finish—like savoring the quiet after an enriching trip.

The Key Factors in Sintering: Where Success Is Shaped

Sintering success depends on more than just heat. Several critical elements work in harmony:

The Dance of Time and Temperature

Too low a temperature, and the body remains weak. Too high, and it deforms or melts. Equally crucial is the rate of temperature change. Controlled, gradual heating and cooling—often with several "holding stages"—ensure even densification.

Like simmering a perfect broth, timing and fire must be just right.

Kiln Atmosphere

The kiln’s firing atmosphere (oxidizing, reducing, or neutral) affects both color and texture. For example, blue-and-white porcelain requires an oxidizing environment for cobalt pigments to develop their signature hue. In contrast, certain reds demand a reducing atmosphere to emerge.

☛ For tea lovers: Why does reduction firing matter for Yixing teapots?

Reduction conditions turn the iron content in Zisha (purple clay) into deep browns and blacks—classic tones beloved in traditional aesthetics. This also enhances the pot’s density, making tea liquor rounder and smoother.

Tapping a well-sintered teapot should produce a crisp sound; oxidized ones tend to be more reddish and muted, suited for aromatic teas like Tieguanyin.

The Alchemy of Glaze

Glaze is a glassy surface coating that adds beauty, waterproofing, and durability. During sintering, glaze melts and bonds to the body, creating textures that range from icy celadon to glossy white.

☛ For tea lovers: How glaze texture influences taste

A smooth, high-fired glaze—like celadon or white porcelain—helps preserve tea aroma.

Unglazed or partially glazed ware—like Jian Zhan or certain Zisha pots—contain micro-pores that absorb trace oils from tea, gradually shaping flavor over time.

Understanding glaze and sintering explains why some say: "A pot develops spirit over time." Every teacup, after all, listens to the tea it holds.

From Handcraft to High-Tech: The Evolution of Sintering

Modern sintering has moved beyond wood-fired kilns to electric and gas kilns with programmable temperature controls—offering precision and consistency.

In fact, ceramic sintering now serves not only teaware but also high-tech fields: semiconductors, bio-implants, and aerospace components.

Yet the essence of sintering remains unchanged: it transforms humble clay into durable beauty.

Common Teaware & Their Sintering Profiles

Knowing the firing range of different teawares helps you choose the right vessel:

- Yixing Zisha Teapots: ~1100°C

Excellent for oolong and ripe pu’erh. Retains heat and enhances mouthfeel through porous yet dense clay. - Celadon Cups (Qingci): 1200–1250°C

Made with kaolin and celadon glaze. Preserves aroma and visually complements green teas with a cool-toned elegance. - White Porcelain Gaiwan: 1250–1350°C

Fine-grained kaolin allows appreciation of leaf shape and liquor clarity. Perfect for tasting a wide range of teas. - Jian Zhan: 1300°C+

Iron-rich clay and oil-spot glazes. Excellent heat retention. Ideal for heavily roasted oolongs and red teas. - Coarse Clay Teapots: 1000–1100°C

High breathability and interaction with tea liquor—perfect for Yancha or rock oolongs. - Duan Ni Yixing Teapots: 1140–1180°C

Made from yellow Zisha clay. Non-porous and flavor-neutral. Great for light-oxidized oolong.

☛ Pro Tip:

Low-fired wares are more breathable, ideal for quick aromatic release.

High-fired porcelain preserves heat and emphasizes sweetness and acidity.

Tap the base for sound quality—clear rings suggest good sintering.

Getting Started: A Beginner’s Journey into Sintering

Curious to try sintering yourself? Here are a few practical tips:

- Know Your Clay:

Low-fire earthenware (<1000°C) is beginner-friendly. High-fired porcelain (>1200°C) requires more advanced tools. - Understand Your Kiln:

Small home kilns are great for practice. Always read the manual—temperature ramping is key. - Start Simple:

Practice with basic shapes and glazes. Every firing is a learning experience. - Keep a Firing Journal:

Record times, temperatures, glaze mixes, and results. You’ll discover your own recipe for success. - Stay Safe:

Always place kilns in ventilated, fire-safe areas. Use gloves, masks, and heat-resistant gear.

Conclusion: The Quiet Power of Sintering

From primitive Neolithic pots to Song Dynasty masterpieces and modern ceramic engineering—sintering has been quietly shaping human culture.

It turns earth into endurance, clay into character. A timeless transformation where heat, time, and intention converge.

Next time you cradle a handmade teacup, remember: it survived fire to hold stillness.

Sintering isn’t just technique—it’s philosophy.

☕ Tea Insight: How to Select Teaware Through a Sintering Lens

- Examine shape uniformity and glaze consistency—uneven finishes may signal firing flaws.

- Tap to hear: clear tones = tight sintering; dull thuds = cracks or loose grain.

- For heat-loving teas (pu’erh, rock oolong), choose high-fired ware.

- For visual clarity (green or white tea), pick fine white porcelain.

- Check kiln marks underneath—well-fired pieces feel smooth even at the base.

- When collecting vintage pots, study the sintering techniques of each era to avoid replicas.